Your Home in Space

Space is trying to kill you. How can you make it feel like home? Sana Sharma is a co-founder and the Chief Design Officer for the Aurelia Institute, where she focuses on creating habitats in outer space that go beyond basic survival. She joins host Sean Mobley to design a cozy place in outer space.

This season of The Flight Deck focuses on space stations. What does it mean to live in space? Stay tuned for a new episode each Wednesday!

Link to learn more about Sana Sharma’s work: https://www.sanasharma.com/

Link to the Aurelia Institute’s website: https://www.aureliainstitute.org/

Link to donate to The Museum of Flight: https://pages.museumofflight.org/flight-deck-donate

Transcript after the player.

SEAN MOBLEY: The Flight Deck is made possible by listeners like you. Thank you to the donors who sustain the Museum of Flight. To support this podcast and the Museum's other educational initiatives, visit museumofflight.org/podcast.

[Intro music]

SM: Hello and welcome to The Flight Deck, the podcast of the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. I'm your host, Sean Mobley. Now, sure, we can make a space station, but can we make it a place that people actually want to live? That's the core question Sana Sharma spends her days working on. She's cofounder of the Aurelia Institute, an organization that wants to make space a home, emphasis on home with all the things that come with the concept of a home. She brought up questions in this conversation that I had never even thought I needed to know the answer to, but, once I heard them, I was like, absolutely. Yes. Like how the heck do you design a couch that works in zero gravity? Sana, thank you so much for joining me today. How are you doing?

SANA SHARMA: I'm doing great. Thank you so much for having me.

SM: You are working kind of a step beyond just dreaming, right? You're looking at the hard science and engineering and also the psychology and all these things about what it would take to actually build a habitat in space. So why don't you tell us a little bit about the work you do.

00:01:33

SS: Yeah. So I'm chief design officer and a cofounder at Aurelia Institute. We're a nonprofit space architecture lab with an education and outreach focus in addition. And so my role with the organization is very much bringing together the human-centered side of space with the engineering and technical development necessary to make new kinds of space habitats real in the near future.

SM: So what does human-centered mean?

SS: That's a fantastic question. For, I'd say, the duration of space habitation as a whole, space has very much been a place that human beings adapt to. We typically optimize the human as opposed to the environment. The goal is to build a space that allows humans to survive and be productive, but who's going to space and how is changing right now. And because of that, there is more incentive to figure out, well, how do we not only optimize the human being but take the onus off of them and place it back on the environment, make environments that are more accessible, more inclusive, and friendly to a diverse set of people and activities.

SM: So what are some examples of that here on Earth. I guess my mind goes to videos of life in Japan where a lot of work has been put into making robots that seem friendly to interact with and stuff like that, but do you have other examples that come to mind?

00:02:57

SS: Yeah. I think with usability and human-centered design, you can see its work in a lot of different spaces, though oftentimes the best human-centered design is a little bit invisible because it benefits everybody in a lot of ways. I think accessibility is a great place to take a look in terms of the ways in which we've modified the environment in order to make spaces more friendly with folks with disabilities or folks who are different on a variety of axis. You can think about, sort of, sidewalks and pedestrian modes of transit.

You can think about the way cars and planes have been designed over the years and the changes that have been made in order to have a diverse number of people engaged in those spaces as well. I'd say from a product design perspective, my background is in emerging technologies designed more broadly. A lot of work has been developed in software and hardware in order to figure out not only how to make something functional, but to make it user-friendly, to make it such that a person can quickly learn and adapt and get used to a [unintelligible 00:03:52] system.

SM: This is grounded in a lot of solid research, and you have a background. I think a lot of people at Aurelia Institute where you work have a background with MIT and research there. Can you share just a little bit about how you learned about this stuff, how you started researching these things?

00:04:09

SS: Yeah. Absolutely. So Aurelia Institute as an organization spun out of the MIT Media Lab. Our CEO, Dr. Ariel Ekblaw, was the director of the MIT Space Exploration Initiative, where I still have a foot over on the research side leading a project called the Astronaut Ethnography project. So the way I got into research for this particular context was through the privilege of—really, really lucky to be able to do this. Reaching out to astronauts, cosmonauts, folks who've been to space in order to learn about their experiences. Not of the mission or the EVA or the research, but what day-to-day life in space looks like.

So what does hamburger night on the ISS look like? What is it like to sleep? How do you get comfortable? What do you do when you get lonely? So those sorts of questions in terms of unpacking what daily life outside of the mission in space looks like very much informed the research on the MIT side. And then as I moved to start working as a designer on the Aurelia side, we brought a lot of those learnings with us in terms of, if we're designing the next generation of space habitats, how do we learn from people who live and work in space right now to make the next generations of environments they participate in all the better for it?

SM: So what were some of the answers you found to those questions? What was hamburger night like? What do people do when they're lonely in space?

00:05:30

SS: I think some of the things that we learned, we expected to see a bit of in the fact that zero-G is a really unusual environment to live in. Human beings are very much optimized for one-G life on Earth. And so existing in zero-G comes with challenges, some of which involved learning to move and to figure out your positioning or proprioception. That's expected. Less expected was the callouses that you'll develop on different parts of your body. So if you imagine you walk in one-G and the soles of your feet hit the ground, in zero-G you're typically using the top of your foot to hook onto a railing or strap to balance yourself. And so how your body adapts is affected in a couple of different ways. We've talked to folks about, sort of, creativity and creative problem-solving in space.

The International Space Station is amazing and has been a tremendous home for research and other efforts, but every once in a while you do need to figure out how to use the space to your advantage. I think my favorite quote from an interview was, "A piece of tape is a table," the idea being that you don't need surfaces to have heft or solidity the way that we would on Earth. Instead, you just need something to be flat and sticky in order for it to hold onto your stuff. That turns out to also be really important because it's really easy to lose things in zero-G. This is the number one complaint we've heard from everyone we've talked to. You don't drop something and it falls to the floor. You let go of something, and it floats somewhere with whatever momentum it has, and you may never see it again depending on its size and where it ends up.

00:07:02

And so these are the sorts of zero-G challenges that were really fun to unpack and learn a little bit about. In addition to those, we had a really interesting time talking with individuals about what communal and social life in space looks like in terms of imagining the future of humanity in space. We're not going as a series of individuals. We're going as a community in a sense. So getting a sense of what that was like, we learned a lot about the role of food in those communal interactions and the importance of food. Research terms that we developed centered around food altruism and food diplomacy, the idea that food is a fantastic bridge when it comes to meeting people, spanning cultural gaps, having a sense of crew solidarity if you all are sharing your treats or coffee or tea together.

We also learned about language in space and the ways in which that related to people feeling like they had more connection and felt more in touch with their home as well as their community, particularly for individuals who spoke neither English nor Russian as their first language. So there was a tremendous wealth of these sort of anecdotal insights that individually might make it onto the cutting room floor of a research paper, but turn out to be tremendous design fodder when imagining new spaces and new interiors that support individuals and support communities in these various aspects or ways.

SM: You mentioned creativity which is always a fascinating topic. We just had a couple of astronauts come visiting the Museum who have different creative backgrounds, like Nicole Stott who painted in space and Cady Coleman who played flute, had a duet with—oh my gosh, I can't remember his name—

SS: Jethro Tull, right? [Ed. note: Ian Anderson is the person who played with Coleman]

SM: Jethro Tull. Yeah.

SS: Yeah. Amazing.

00:08:47

SM: …Cady Coleman, who had a duet with Jethro Tull. And you talk to a lot of astronauts, and they talked about music [unintelligible 00:08:52]. I just think that that's one of the things that gets people excited about space because, when you think of Star Trek, right, everyone's always working on an art project. Someone's sculpting or things like that. How much real science is the inspiration here, and how much is science fiction, those kind of idealized versions of the future where people have time and space to do these things?

SS: On the subject of art, just to take the point beforehand, it's something that I believe is really, really valuable in space contexts even in high stress, sort of, high productivity environments like today on the International Space Station. Art isn't frivolous. It's a fantastic way for individuals to destress, to connect with others, to connect with home. You brought up a bunch of fantastic examples. There's also been calligraphy aboard the International Space Station. There has been, again, the sharing of food and other sort of cultural elements. These sorts of things—photography is a huge one in terms of how you might capture the experience of being in space and share it back on Earth. All of those things are incredibly valuable both to the astronauts in situ as well as when connecting with us back on Earth. So I am a big fan and a big proponent of the value of the arts in space.

00:10:07

On the subject of science fiction, this is really interesting question for us both on the MIT side as well as on the Aurelia side. The mission charter for the MIT space exploration is to develop the artifacts of our sci-fi space future. And so science fiction is very much part of what inspires a lot of the work that goes on. And I love Star Trek as a reference. It's probably my favorite science fiction in space story or anthology out there because it does such a fantastic job of taking this extraordinary thing in terms of life in space for long durations of time and making it feel like home, making it feel comfortable.

One of the interesting challenges though with designing with sci-fi in mind is that what I found is that we tend to, sort of, recycle a series of tropes and visualizations, that there's this defined aesthetic when it comes to what the future is supposed to look like that we've pulled from a couple different cultures, a couple different agencies, a couple different visions. Something I find very exciting about moving maybe not even beyond sci-fi but broadening our horizons when we imagine the future is that we can learn from so many people about what might motivate them to engage with space in the future, and complicate and diversify those visions as a result. That's something I think we play with on the Aurelia side. We have this Western, 20th Century vision of what the future of life in space looks like. Well, where else can we pull from in order to evolve or iterate or expand upon that idea?

00:11:38

SM: Yeah. There's even conversation around the vocabulary that we use for stuff like this. For example, talking about colonizing another planet and the word colonize has a—is a hefty word to use. Some might not think about it, but for other people, you bring up the word, "Oh, we're going to go colonize Mars," there's a lot of implications that other folks don't think about when we use kinds of words.

SS: Yeah. I think when approaching these sorts of things, we have a lot of terrestrial baggage that we bring to space, and I think we have the opportunity and responsibility to learn from a lot of that terrestrial context as we engage with space moving forward. At Aurelia Institute, we're really, really interested in space for the benefit of Earth, so how might we increase real estate in terms of how we can build in space and support more people but with an eye to supporting research and other activities that then support Earth, and having that sort of cyclical beneficial connection between what we do in space and what we do on Earth.

SM: And that's where I think it's really interesting to center these universal design principles you talked about. For example, you said earlier that astronauts on the Space Station use a strap to strap in their feet if they need to stay in place, and that presupposes that the astronaut has feet. And in a future with millions of people living and working in space, going to be all sorts of people up there who have all sorts of different needs. So can you talk a little bit more about how some of these design principles and designing for space with access in mind? First of all, what does that mean? What are some things that able people might not think of? And then, second of all, what might that kind of stuff imply, or how might that kind of stuff improve life on Earth for people with disabilities but also everybody?

00:13:32

SS: Mm. That's a big question. I think when it comes to—

SM: [Laughter]

SS: Yeah. It's a big question, and it's an important one for us to work through. And as I answer it, I want to shout out a group called AstroAccess, which does fantastic research and advocacy work in this space. I've learned a lot from them over the past several years. We've had the opportunity to work with folks from AstroAccess on both the MIT and the Aurelia side. But when it comes to the risks of universal design—maybe let's put it that way—I think we've traditionally, whether it's been because of constraints or it's been because of the way we've worked on challenges in the past, have developed a set of one-size-fits-all approaches to some of these design aspects, again, with the goal of having the human adapt to that system.

However, I think we have the opportunity to move away from that sort of universal design system into something that's more inclusive, systems that are modular, that are reconfigurable, that adapt to the needs of the people they engage with. To give you a very, very simple one, zero-G environments like the International Space Station can be increasingly challenging if you're on the petite side. I've gotten to experience a little bit of this firsthand on a parabolic flight, if you're familiar with vomit comets, but if you can't touch a wall surface or railing, you live there now. It's very hard to move around. You can't necessarily swim in space with any efficacy.

00:14:53

I've heard stories of astronauts needing to essentially tie their sleeping bags to make them shorter so that they don't bounce up and down in the sleeping bags at night. That's a really, really simple example of the sort of universal standard that was implemented that didn't actually work based on an axis of variation that's pretty common for human beings. So this is something that I think we need to do a lot more work in, but we also have a tremendous amount of opportunity to make better when it comes to designing for zero-G in such a way that we can host more people in space comfortably.

SM: The dreaming, the conceptualizing is all well and good, but the folks who say that this needs to be really practical—you talked about modularity. What work are you doing around making sure that these ideas have these practical applications like—why don't you talk a little bit about TESSERAE, what it is. A lot of people think it's named for one thing, but I have learned that it is not named for that thing, so even the name I think is a fascinating little piece.

SS: Interesting. I'd loved to know what your initial notion of what TESSERAE was named after.

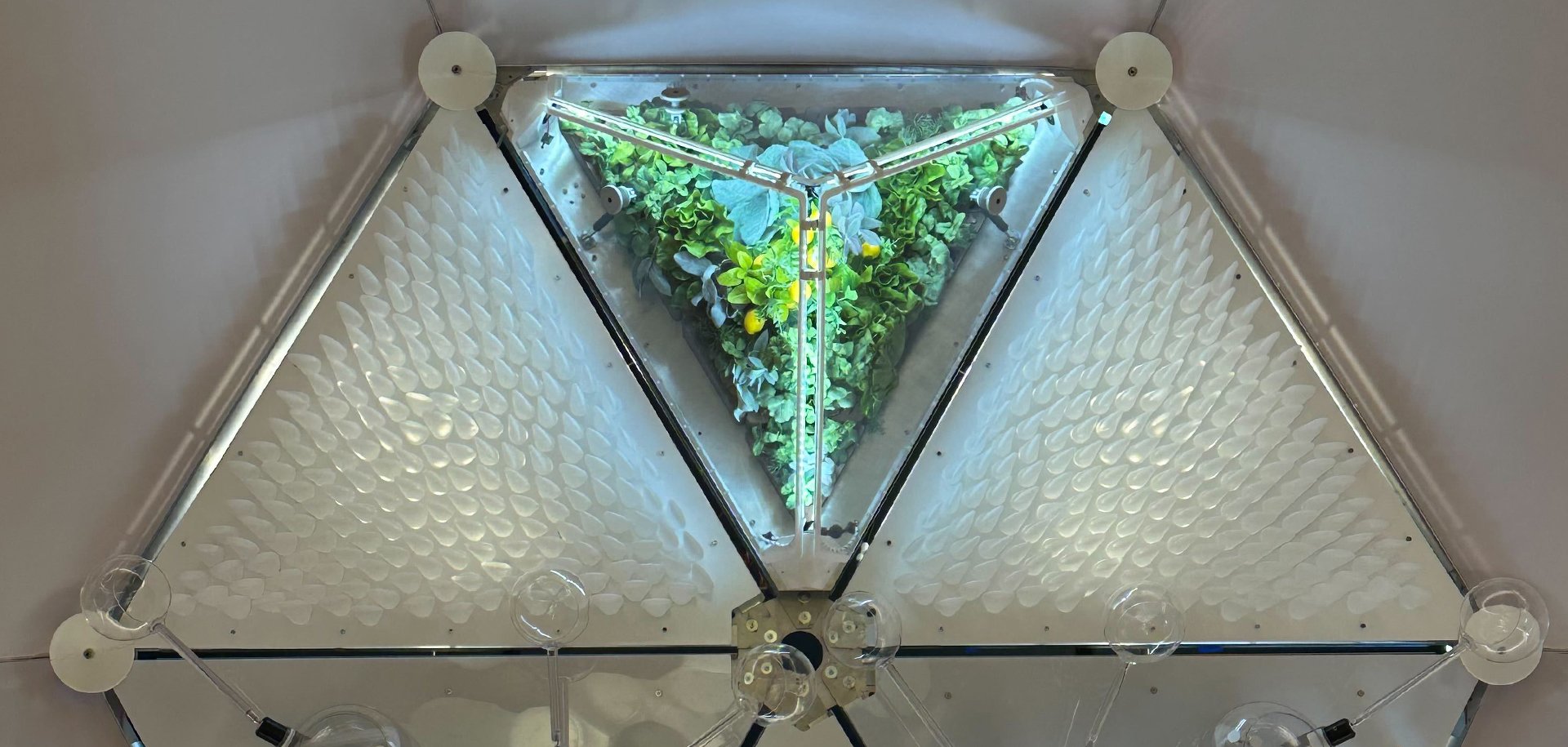

SM: Well, I and most people who—everyone who I've talked to about it—for the listeners who don't know, the TESSERAE Pavilion was on display here at the Museum, and it's an example that the Aurelia Institute built of what you're working towards. And it looks like a giant—what shape is it?

00:16:21

SS: It is a truncated icosahedron is the technical name.

SM: Right. [Laughter]

SS: Soccer ball shaped is maybe a bit more, yeah, general.

SM: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Soccer ball. Those panels actually work really well as a soccer ball.

SS: Hm-hmm. [Affirmative]

SM: But, anyway, so I was under the impression that it was named after the mathematical thing or even a reference to A Wrinkle in Time, but in talking with the folks at Aurelia, I learned it actually has a very different name, origin story.

SS: Yeah. So I can tell you about that. So TESSERAE is an acronym, as many things in the space industry are, for Tessellated Electromagnetic Space Structures for the Exploration of Reconfigurable Adaptive Environments. It's a long title, but TESSERAE for short. I hadn't considered the Wrinkle in Time parallel, but it is very much meant to harken to tessellation in terms of how one can lay out in pattern regular shapes because that's very much the name of the game in terms of the architectural paradigm. TESSERAE essentially is designed to work such that you have a series of tiles, hexagons and pentagons, that stack flat in the payload fairing of a rocket, get sent into a zero-gravity environment like lower Earth orbit, are released, and then stochastically self-assemble using electropermanent magnets into the soccer-ball shape, into this truncated icosahedron.

00:17:45

The value of this paradigm is that you're able to build volumes much larger than the rocket itself through the use of these modular tiles and panels. And, ideally, we might be able to, if a particular tile or panel is experiencing an issue, to swap it out, so to build it in a slightly more modular and sustainable way. This paradigm, ideally, if we do our jobs well, in the future might allow us to build several of these truncated icosahedrons, these soccer-ball shapes, and attach them over time allowing us to grow organically a size and volume of space habitat we might need based on the needs of the crew and the people it's supporting.

SM: So, basically, imagine that soccer ball but where each side of the soccer ball could be removed as needed and replaced or removed and put into a hallway that can connect to another soccer ball.

SS: Hm-hmm. Hm-hmm. [Affirmative] And then attaching those individual modules, those TESSERAE balls together in order to form a larger complex shape comprised of these individual soccer balls or truncated icosahedrons.

SM: Well, then, will you indulge me a little bit? Because I think a fun way to imagine this would be to put ourselves into it. So will you help me build a home in space here for a couple minutes?

00:19:00

SS: Yeah. That sounds fun.

SM: And listeners, I encourage you to think of your own answers to these questions as we go along so you can imagine your own home in space. So if we're going to create a TESSERAE for Sean, where would I even start? What should I be thinking about in terms of what I would even want to have inside this facility for me?

SS: Yeah. That's a fantastic question. On the architectural side of things, we'll talk about this in the context of programs. So what are the activities you're trying to support in a volume like this? Now, for places like the International Space Station, you have working areas, so your research stations, research racks. You'll have living areas, so crew quarters, places to sleep, places that are quiet and clean and can be individualized.

You will have maybe messier and louder spaces, particularly exercise, which is really important in a zero-G environment to maintain health as well as food, so cooking, dining, preparing, coming together to eat, as well as hygiene, which is very important and quite challenging in space. How you stay clean and how you maintain the cleanliness of your environment. So those are some big buckets to think about in terms of what a human being working in space might need at a baseline. But to you, then, the question is, well, what other spaces would you want to see in this ideal home for Sean?

00:20:26

SM: Okay. Well, let's say, in this version, I'm doing what I do now, so it's a lot of informal public education. So I'm a podcaster in space [laughter] sharing with people about what the experience is and the science that's happening and chatting with cool people in space and beaming it back down to Earth so that everybody else can enjoy it. So I guess a question I would have then back to you is, in this version of the future, do you imagine families in space or individuals in space, or what is it that you see using these kinds of facilities?

SS: I think it depends on the time scale you're discussing. And so the near term, I think we're very, very interested in this novel way of building for space in order to support a lot of the existing work that's happening right now but maybe evolving the ways in which it's done. So supporting crews that are maybe a hybrid of NASA and other agency astronauts as well as research specialists, tourists, other individuals who want to come up into the space environment but aren't career astronauts. Supporting that community and how they live together in orbit and how they manage to do the things they need to do without getting in each other's way.

You mentioned podcasting and recording and the acoustic sensitivities associated with that line of work. Acoustics in space are an interesting challenge. There is a sort of natural hum or din when it comes to running a space station, which may impact the work that you do. However, we've also heard from individuals who've lived in these environments that there's a certain amount of comfort derived from hearing the ship working as intended, and so there are these interesting tensions of you have a lot of different people doing a lot of different things. How do you support those different activities?

00:22:12

Families gets interesting. I think it is currently an unknown that people are researching and looking into in terms of how you might support younger individuals, how you might support families, what long-duration life in space might look like given that in terms of cumulative amount of time in space, we're still measuring in days and then to the couple of years. So that's a lot of work that needs to be done in order to figure out, well, you have communities in space that are maybe working together, coming up, coming down on different timelines. To know there's a community who lives here for an extended period of time who maybe are related or have community relationships with other individuals here. That's a long scale, long term, and very interesting thing to work toward.

SM: Yeah. And there's—I think it's outside the scope of this conversation, but, I mean, there's even ethics questions about if people reproduce in space, you're now essentially having a baby that's an experiment. [Laughter] And what does that mean ethically and what's the responsible way to do that? That's, I think, maybe outside the scope of this discussion.

00:23:21

SS: Zero-G is a challenging environment is maybe the thing to say, and we have a lot to learn about what it takes to keep human beings happy and healthy and safe. And as we learn that, we can start extending and expanding how we might evolve the ways in which community interacts in space. Yeah.

SM: Well, so, getting back to your question about what kinds of things that I would need, well, I think, for one thing, my computer setup here to be doing the recording and the editing—and hopefully it's not running on Windows XP like I think the ISS computers still are if I'm not mistaken. But, also, let's see. Well, I got ADHD, and so there's not going to be tables upon which I can leave the clean clothes that I have folded. But, yeah, what kind of storage solutions would we have for just the tritest of everyday life?

SS: Ugh, storage is a fantastic question and maybe a perennial sore topic when it comes to living and working in space environments. Again, it's really easy to lose things in space. It's also hard to store and keep track of things. And I know RFID solutions have been suggested, sort of organization solutions, but if you can imagine putting things into a bag in zero-G, they're not all going to settle in a direction. Things are going to float about. Thing are going to move around. So this is something that's genuinely challenging.

00:24:39

On the Aurelia side, we've been looking into different ways of designing a zero-G pantry. The core story that we've been telling with the TESSERAE Pavilion, the full-scale structure that we've had the fantastic fortune of sharing with patrons of the Museum of Flight this past fall, has been around growing, cooking, and eating food in space, sort of the idea of breaking bread in orbit. But in order to do that, you're absolutely right. You need a place to store and maintain stuff. And so whether or not that's bottles or you're wedging things into snug nooks as a way of solving storage issues, whether the goal is to essentially have things visible as storage, these are all elements that we might be able to play with.

I think there's also tremendous opportunity for sort of modular solutions in this space. Again, if a piece of tape is a table, a chair might be a strip of fabric held taut, or a couch might be an inflated pillow that you can sort of lean into. And so what might we be able to do with soft and squishy architectures to not only house and make us comfortable, but to keep track of our stuff as we try to use this limited space as a resource for a number of different activities.

SM: So what you're saying then is that this is not an environment where you can just leave the hammer out on the counter both because it won't be on the counter. It'll float away. But, also, because in this communal space, other people are going to be looking for that hammer and it's—obviously, if you leave it on the counter on Earth, maybe someone can find it. Maybe they can't. But when the counter has no gravity necessarily, then the hammer might be off in another room all of a sudden before someone else needs it. So this kind of organization, yeah, it's a good point. It really sounds like it's a key part of all this.

00:26:27

SS: The status quo solution is Velcro right now in terms of being able to keep something visible but placing it down. A table is a piece of Velcro where you can stick something to hold it in place. But I think there's interesting potential for innovation not only in the environment design but also for the embodied design, sort of what you're wearing in space and how you might keep track of things. On the MIT side, I had a colleague develop a zero-G apron that she was able to hook on to a surface and then, in zero-G, use her body to extend in order to produce a table in front of her that she was using to knead dough.

The idea being, yeah, maybe instead of storing things in places, if you're working on something, you're storing things upon yourself or upon maybe a caddy or a tail or an appendage that you've developed in zero-G to keep track of the things you want to keep track of. Now, sharing and communal objects, that's a whole separate challenge because it's not only you who needs to keep track of things but the folks you're working with and the people around you. That is tough.

SM: Your point about seating in couches is really interesting because if we go back to sci-fi again, too, in that Star Trek future, it presupposes gravity on something like a space station, but the reality is in zero gravity, what use is a couch? Because we haven't been to space, right? So, I mean, I get it. It's hard for me to understand. But if you try to sit on a couch—lets say you've got your Ikea couch in space. If you try to sit on it, just the way it works is it will be moving away from you because the second your rear end makes contact with it, that's putting force onto it, and now it is going to start floating away from you. So something like a couch is so much more difficult to design than people might imagine.

00:28:13

SS: This is one of my favorite topics when it comes to interior design in zero-G in that the lexicon, the vocabulary of things that we use on Earth, like tables and chairs and other kinds of furniture, are going to have to be fundamentally rethought when it comes to using them in zero-G. And the couch is a really good example. Even if your couch is bolted down onto the side of a wall, if you tried to collapse into it without gravity, you're not going to sink into that couch. And so the question becomes less how do we design a couch in zero-G, and more how do we make an environment that is comfortable, that is relaxing, that allows you to release muscle tension and stay put while getting that feeling of warmth or comfort that you might expect from a terrestrial couch experience?

This is something we directly prototyped when it came to the TESSERAE Pavilion. We were quite inspired by sea anemones and clownfish, the idea that clownfish will sort of nestle in between the tendrils of a sea anemone for protection as well as for comfort. And we wondered whether or not we could approximate, with an inflatable structure with tentacles and bulbous elements that come out of the wall, a similar object that a zero-G individual might be able to nestle into and position themselves to stay comfortable. And so the form factor is fundamentally different, but the desired outcome is very similar in terms of comfort and relaxation.

00:29:36

SM: So this is a bit of what you were talking about earlier when you said science fiction in a way limits us?

SS: Mm.

SM: Right? Because I don't know that the sea anemone design—and like you just said, Sana, listeners, yeah, imagine truly the fronds of a sea anemone that you could nestle yourself into. That's what is on display in the prototype, but that's not something that necessarily is going to show up in science fiction. It takes a little bit of a different approach. I mean, it can. There's nothing saying it can't, but—

SS: Yeah. It hasn't yet, but maybe it will in the future if we're lucky. This is where I'm really excited about using sci-fi as one of those inspirational tools because so much interesting work has been done in that space in terms of thinking through desirability and feasibility and really out-there concepts, but layering onto that embodied knowledge that we can gain from people who've already been to space who tell us about the things that are maybe counterintuitive about living in that environment. Maybe opportunities to make things better or different as well as then that layer of biomimicry or biophilic design. It's something that we're really interested in on the Aurelia Institute side, and it's where we often pull from when trying to solve some of these unusual or counterintuitive challenges. We may not have an immediate human analog, but maybe we can learn from a sea anemone to help us with this particular design challenge.

00:31:00

SM: All right. So I've got my podcasting setup. I've got my sea anemone couch to chill at the end of a long day of podcasting. [Laughter] So you've talked about food then. Let's talk about that a little bit more. What should I be thinking about in terms of making sure that I have a space for myself where I can prepare and share food with the social component assuming I have to go up just myself, leaving family behind and am now working with a crew of other people in a similar situation? What should I be thinking about?

SS: There are a lot of interesting challenges associated with growing, cooking, and eating food in space. The status quo currently involves, for the most part, reheating and rehydrating dried foods in packets. You can see a briefcase that's used for this process, or something that looks like a briefcase, on the International Space Station, though there's been innovation. I know there was an oven developed to cook or to bake cookies. I know there was a zero-G espresso machine that was used for a period of time. Don Pettit's beautiful zero-G coffee cups are, I think, a fantastic example of the ways in which we might change cups, bowls, cutlery, food apparatus when it comes to enjoying food in space.

00:32:15

But the challenges are interesting in that, for one, crumbs can be at best a nuisance and, at worst, a fire hazard. And so you'll often see, in lieu of bread, astronauts using tortilla as a non-crumb, fire-friendly carbohydrate that they can eat. And so you may be rethinking, okay, what kinds of foods am I going to bring to space in order to be safe and tasty? We've heard individuals talk about the monotony of eating the same food every day and, with an international crew, swapping meal packets and trying out different flavors. We've heard stories of individuals trying raw garlic for the first time just because they wanted a different taste. They were a little bit sick of the food that they were eating as well as the importance of hot sauce and other condiments as ways of supplementing and providing variety. So increasing the variation in terms of flavor of food as well as nutrition and making sure those two things are paired becomes really, really important.

On the Aurelia Institute side, we've been looking into fermentation as a way of providing shelf-stable, nutritious-but-flavorful food in terms of supplementing and adding variety to the diet of a spacefaring individual. We've developed a fermentation station which was one of the functional tiles that we'd installed into the TESSERAE Pavillion, the large-scale habitat. Then I think the last and interesting question is, okay, you're growing some food maybe through hydro-aeroponics. You have your maybe fermented foods. You've brought things up with you that are tasty and nutritious but also safe for the environment. You've probably taken weight into account in terms of how much water or mass each of these food elements has.

00:33:53

Now, the question is how do you eat that food or share it with others as well? So advances in a zero-G kitchen, thinking about what a zero-G dining table might look like given you don't necessarily all have to sit in the same orientation if you don't want to. There's a fantastic couple of photos of individuals floating above the dining table aboard the International Space Station when dining gets a little bit crowded, and there are a lot of people on the Station trying to eat at the same time. There are a lot of different, interesting ways to approach making that experience not only nutritious but also pleasant and maybe community-building as you and your fellow crewmates use that time to check in and make sure everyone's doing okay.

SM: Is part of what you're doing industrial engineering then, like developing the processes by which these things will happen and not just the actual spaces that they happen in?

SS: Mm. We've been working on, I think, a variety of different scales of technology at Aurelia Institute. That might be the best way of describing this because we're interested not only in the self-assembly paradigm but, as you've put it, how we might use that space once it's assembled. And so in addition to our space-worthy hardware, we've been able to task a smaller version of our tiles on the International Space Station through astronaut interaction payloads. We've also been working at this full scale through things like the Pavilion to help us not only communicate what life in space might look like, but also develop research elements that we can then test to figure out whether or not these elements or components of this life we're designing are meeting the fidelity and rigor we'd need to see for them to be usable and useful in space.

00:35:32

SM: Now, for people who are interested in a deep dive into space food, I will recommend a podcast earlier in this very series where we talked with Vickie Kloeris, who was a major driver of the food program down at NASA for years. So check that episode out on our archives. But lets move on. We've done food. We've done work. We've done a little bit of comfort. Let's talk about the other part of this which is just the things that will keep you sane through this whole process, right? You talked about earlier what people do when they get lonely or what people do when they get homesick and things like that. So stepping beyond the work and the truly functional sides of things, what should I be thinking of in terms of emotional comfort, creativity, down time, things like that to have with me in this home in space, in my personal TESSERAE?

SS: That's a fantastic question and something we're excited and optimistic to see have a little bit more real estate as we're able to expand the amount of space human beings can use productively in orbit. Taking care of yourself in space can be challenging. It's an extreme environment, but it's also, depending on your job and what you're responsible for, you might be responsible for a series of fairly rote tasks. You might be responsible for challenging emergency situations. Even as a podcaster, even as a tourist, you're going to keep in the back of your mind the element of safety, and so how do you relax and take care of yourself in an environment that is extreme?

I think one thing that's really valuable in terms of the status quo that would be incredibly helpful to have is a form of exercise. Exercise is very, very good for health, but it's also very good for mental health when it comes to maintaining yourself in space and in zero-G environments over long periods of time. And so that's definitely a must. In terms of self-care, we've heard of the arts and creativity being used as ways of taking care of one's self, checking in, allowing spaces for rest and reprieve.

00:37:36

Sleep's also a really important factor in this, and making sure that you've carved out an environment or space that suits how you sleep is really valuable. Because sleep is one of those things where we are all a little bit different in terms of how we approach it, what's going to feel comfortable particularly in an environment like zero-G, whether or not you really want to be swaddled, for instance, in a sleeping bag, or if you want to float around a little bit and that actually feels a bit more comfortable for you. We've seen or heard variants in terms of how people experience that.

Then in terms of homesickness and connection to home, that language element's been really an interesting one for us in terms of talking to a participant on our end who I don't think realized how lonely they were until they had heard—they were working on an experiment in their mother tongue, in their native language, and realized that that had been the first time they'd actually heard that language in a minute. And that gave them a moment of pause. But this is something that I know as we've had the ability to connect via e-mail and calls through the increasing availability of media in low Earth orbit, which wasn't a given when the Station was created. Those are various things in terms of touchpoints from home, both in terms of talking to friends and family as well as engaging with media and culture from your home environment, that provide a lot of value.

00:38:52

Then I think there's the crew itself. I know I've mentioned food a lot, but it turns out that the dining table in that locus where everyone comes together turns out to be a really important moment for crews that have taken advantage of this for people to check in and make sure that folks are doing okay. Because space can be challenging. And so having environments and moments and spaces that are designed to help people take care of each other are definitely worthwhile when it comes to living and working in environments like this for long periods of time.

SM: What do you think a sport or dexterity game created for space from the ground up might look like?

SS: That is such a good question. I've seen examples of astronauts using rolled up pieces of paper and balls to hit and play makeshift tennis. It's challenging because you're floating, the ball's floating, everything has different amounts of momentum. You're all moving in different directions. It's chaotic. I think an ideal sport for me would have to thread the needle between embracing that chaos in terms of momentum moving and directionality with having just enough structure that it feels competitive and not totally chaotic. And so what that looks like is a really fascinating and interesting thing. Maybe it does involve throwing or kicking a ball or other surface with the consideration that when you let go, when you throw, you're giving momentum to yourself as well. There's a lot of space to play in that area.

00:40:16

SM: When we talk about cultural things, too, there's whole other layers of complication that come up just naturally. For example, some people's religious—have religious ceremonies or ideas that involve where sunup and sundown is important or directionality is important. And these things have been studied. How does a Muslim face Mecca if they're in space with extra dimensions and things like that? More and more of that will have to be thought about as more and more people go to space.

SS: Yeah. Absolutely. And I think it's one of the best opportunities for cultural exchange as well is to figure out some of those interesting challenges for how you bring a part of yourself to space and in that environment pay homage or respect to the culture you come from. We've held festivals and holidays in space. The varying ways we do that is a fascinating thing. I know there was—I believe an astronaut brought cherry blossoms, if I'm remembering correctly, to the International Space Station to pay respect to their Japanese heritage along with a Japanese musical instrument. And those moments of not only bringing those elements with them but also being able to share with the crew turned out to be a great way to bring the crew together. As you have individual members from different cultures, you also have ideally a burgeoning space culture in terms of this one crew working together to take care of each other.

00:41:37

SM: What gets you excited about your work?

SS: That's a great question. I think I'm incredibly privileged to work on the things that I work on. Space is something that I've always been interested in. I thought I was going to be an astrophysicist growing up, but took a hard pivot in undergrad and got an architecture degree instead. But I think there is something really fulfilling about taking a space that's traditionally been pretty rarified, where you've had to have been among the few most resilient, adaptable individuals in order to engage, and start to peel away at that assumption. And figure out, well, how do we design and build such that we might be able to, again, make environments that are more inclusive in terms of who we can support? And there's a tremendous amount of work to be done, but there's also—we are only able to do the work that we've done because of all of the work that's come before us. And so it's a really, really exciting time to be asking these kinds of questions and working in the industry.

SM: Well, Sana, thank you so much for indulging me and helping me build this—I'm excited to take this trip to space now and check out this spot. Where can I go get my ticket?

SS: Well, if you're interested in learning the path to development when it comes to building out these space habitats and experiences, I'd recommend checking us out at Aurelia Institute. We're at aureliainstitute.org and on your requisite Instagram, social media. We've had a pretty big year in terms of both work in the spaceflight context as well as in this big human scale, sort of human-centered design, and we're doing a lot in 2025. So we hope you'll come along with us.

00:43:09

SM: Awesome. Well, again, Sana, thank you so much for your time.

SS: Thank you so much for having me. This was fun.

[Outro music]

SM: Thank you for tuning into this episode of The Flight Deck, the podcast of The Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. We've got links to Sana's work and the Aurelia Institute in this episode's show notes, which you can find at museumofflight.org/podcast. The Flight Deck is made possible by the Museum of Flight's donors, everyday people who are just excited to share these sorts of stories. Special thanks to all of you for your support. If you like what you heard, please subscribe to the podcast on Apple Podcasts or wherever you downloaded us from. And please rate and review the show. It really helps spread the word. Until next time, this is your host, Sean Mobley, saying to everyone out there on that good Earth, we'll see you out there, folks.