A Century-Old Conspiracy

An aviation conspiracy dating back 100 years continues to capture the imaginations of New Zealanders. What’s the truth behind this story, involving secret caves, military secrets, and the first Boeing airplane? Host Sean Mobley sat down with Museum of Flight Docent Leslie Czechowski to dig into this curious episode of aerospace history which spans continents and centuries.

Your support of The Flight Deck makes the podcast possible. Learn more about making a donation at this link.

During your next visit to The Museum of Flight, make sure you look up once you enter our Great Gallery to see the B&W Replica. More information on our aircraft is at this link. Plan your next visit to The Museum of Flight at this link.

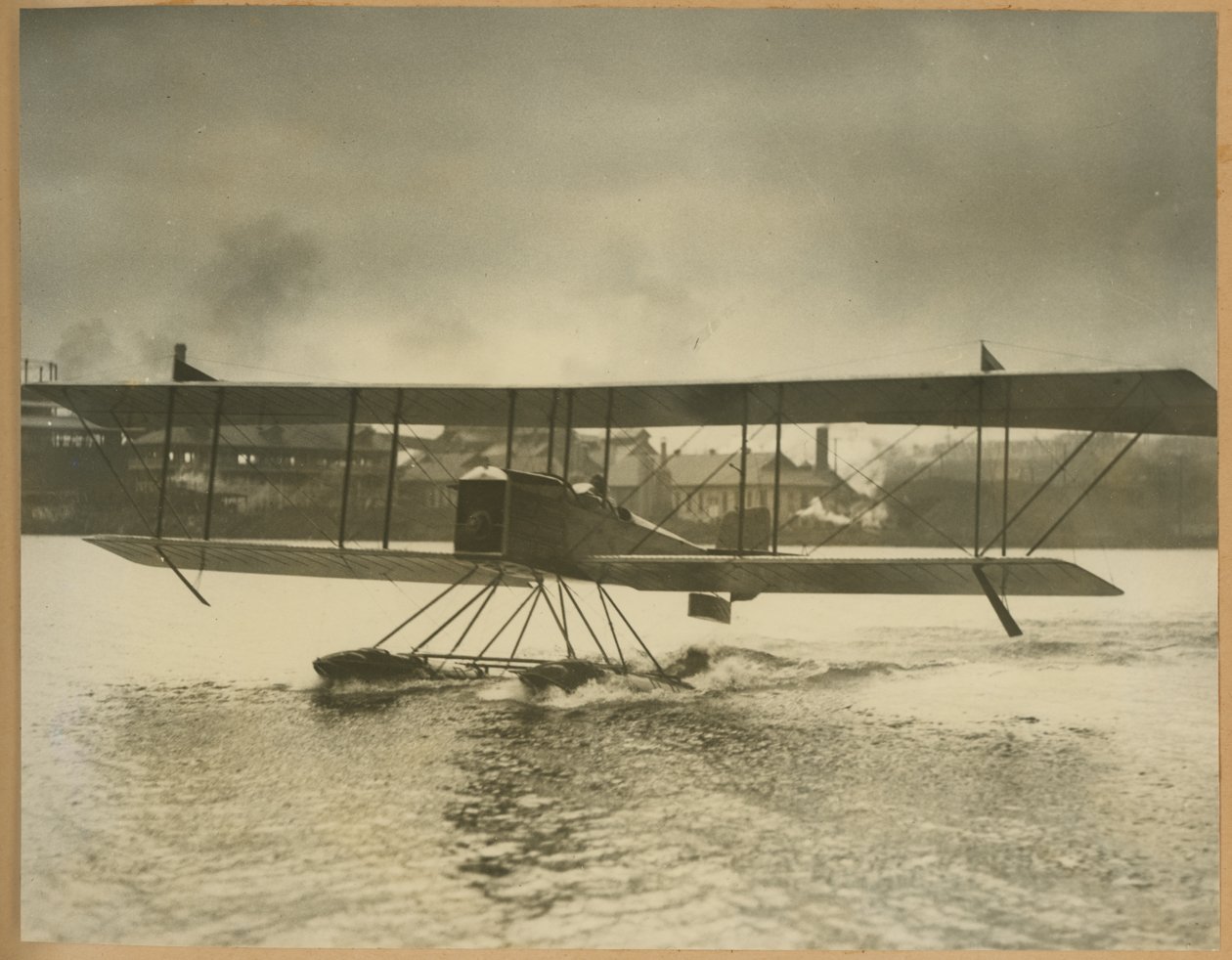

Check out a vintage image (ca. 1913) of the original B&W in our Digital Collection at this link. Would you want to take it for a spin?

Learn more about The Museum of Flight’s remote offerings, including education programs, 3D tours of aircraft, and more at this link.

Credits:

Host/Production – Sean Mobley

Production – Megan Ellingwood

Social Media Specialist – Tori Hunt

Layne Benofsky - Webmaster

Transcript

00:00:21

SEAN MOBLEY: Hello, and welcome to The Flight Deck. The Podcast of the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. I am your host, Sean Mobley. Today, we’re taking a virtual trip all the way from Seattle down to New Zealand, tracing the journey of Boeing’s oldest aircraft, the B&W. Now if you’ve visited the Museum of Flight, you might have seen a replica of the B&W hanging in our Great Gallery which was manufactured by Boeing for an anniversary. But the original B&W has taken on a life of its own in New Zealand where it went from an unassuming, century-old aircraft, to the subject of conspiracy theory documentaries and lawsuits. Who knew that a century-old plane would be wrapped up in so much intrigue? I want to remind listeners up front that conspiracy theories are just that—conspiracy theories. They are often unsupported; based on fabricated evidence or shaky evidence and often completely fall apart if even just one piece of the theory gets removed. So with that in mind, I caught up with Leslie Czechowski, one of the Museum of Flight’s docents, to get the real story. So let’s start off with the B&W itself. What makes this aircraft so important in aviation history?

00:01:53

LC: Well, it’s very important because it was the first plane that was built by the Boeing Company. Actually, it was built before Boeing actually became a company. There were two of these float planes built. They were called B&W because Boeing built them with his partner, Conrad Westervelt, and they built them and hoped that they would be able to sell them to the US Navy for use in the war—because, of course, this was during the 1st World War—but the Navy didn’t want them; they sent them back. And so Boeing was looking—at this time, it was the Boeing Company—was looking to get rid of them. Now, there was a letter that I was able to locate; given my interest in doing historical research, I had access to the Boeing Company archives and found a letter from the head of a company called the Hall-Scott Motor Company who sold engines, airplane engines, to both the Boeing Company and to an organization in New Zealand called the New Zealand Flying School. And so when Boeing was ready to get rid of the planes, this was the way that the New Zealand Flying School found out about them.

SM: Now for the plane nuts out there in the audience, can you tell me a little bit more about the B&W itself—what made it interesting from a design perspective and what were they trying to do?

LC: I’m not sure I can necessarily answer it. It was a good plane. I think they were thinking that they could use it for travel here in the Seattle area; especially flying over bodies of water to get to places that you couldn’t get to otherwise. And then, as I said, to sell to the Navy for use. It was a good plane and for some reason or another, they weren’t able to convince the Navy to buy it; although, to be truthful, by the time they were trying to sell it to the Navy, the plane was two years old. It was built in 1916 and they were trying to sell it in 1918 and, in those years, of course, development was very rapid in terms of improvements in airplanes. So that may have been why they weren’t able to sell it to the Navy but I’m not sure I can answer much more about it. I’m sure there are others who would know a lot more about the details of the plane than I.

SM: Yeah, you make a good point—people think of Seattle as a rainy place; they don’t realize just how much water is already on the ground around here. A sea plane would be a pretty useful tool.

LC: Definitely.

SM: So the Boeing Company has lined up a buyer in New Zealand. So how did they get the plane down there? I imagine there was no Internet for them to send pictures back and forth over e-mail and then ship it down there via overnight post.

00:04:39

LC: No, indeed. And it’s fascinating to read correspondence from those years. The mail must have gone very quickly between the United States and New Zealand and, of course, the people that bought the plane were in Auckland, which was the capital of New Zealand, so there’s a number of letters in the Boeing archives of part of the exchanges between the companies about the purchase of the planes. And then the planes themselves were taken apart and put in big crates, loaded on a ship, and they just sailed them down to New Zealand. I guess shipping was an important way of transporting things across oceans back in those days.

SM: Did they fly the plane in, once it landed?

LC: No.

00:05:22

SM: Or did they ship over land?

LC: There’s a fascinating photograph that I found. It does not show the way they got these exact planes to the flying school, but it does show a large crate on top of, like, a flat-bed trailer almost that’s being pulled by four horses. So there you have an airplane, in pieces, being pulled by four horses, which is kind of a wonderful juxtaposition of two different technologies that are tied in the world when those two were competing with each other, in a way.

SM: What exactly was the flying school hoping to accomplish with these planes and what did they actually do?

LC: Well, they were, as I said, a flying school and they did a lot of training people to fly. As everywhere, there were a lot of people interested in learning how to fly. They also had a number of students who were learning to fly to become part of the Royal Air Force and they trained a number of them, since New Zealand is part of the British Empire, they contributed a lot of men to be in the British services. But they also ferried passengers back and forth around New Zealand and delivered mail, for example, so all-purpose airplanes for a variety of purposes. Now, the planes were not equally adopted by the flying school. Boeing had given the planes names—they called them Bluebill and Mallard—and the flying school gave them different names. The flying school just gave letters to all of their airplanes in the order in which they bought them so Mallard became G; and Mallard, after they put it together, just didn’t fly very well. And they made some adjustments in the plane; they added ailerons to the second wing and all sorts of things, but it just never flew very well and so they didn’t use it very much. However, Bluebill, which was assembled in January of 1919, became a star performer for the flying school. And in it, their chief pilot, George Bolt, set a number of important records in New Zealand that really puts New Zealand’s aviation history on the map—or at least what people in the New Zealand area think was on the map—and I could tell you some of the details of that if you’d be interested?

00:07:51

SM: Sure, I’m just imaging an alternate universe where Boeing had stuck with bird names for their planes instead of numbers.

LC: I know, wouldn’t that be fun. So Bolt really did like flying Bluebill—or F as they called it—and talked about how it was a very fine bus—that was the term that he used, which I think is kind of charming. He thought she was steady to fly and he noted that these two planes were the biggest all through Asia and so he managed to set out right away after the plane was put together and tested. So, in January of 1919, he set an altitude record for New Zealand. They reached about 4,000 feet and then the climb from that point became very, very slow so it took an hour to go the additional 2,500 feet that they needed to go to set the record. And, interestingly, the altitude was measured by a barograph that he had strapped to his knee so it was an unusual way to do that.

00:08:51

And then when they came down, he just turned off the engine and they volplaned about 6,500 feet to get back to the ground in under 10 minutes, so it was quite an interesting adventure. About a year later, in December of that year, he flew the first airmail flight in F; the first one in New Zealand. And I think this is kind of a charming story, also. You know, if you know much about New Zealand, you know that it is surrounded by water, of course. And much like Seattle, there’s a lot of water that people might want to fly over to get various places, but you can fly over land. But when he got the contract for the airmail delivery, the chief post officer in Auckland was a little nervous about this whole flying mail thing so he told all of the post officers all over the route that they were going to fly, that they had to watch overhead and then when they saw the plane flying over them, they had to telegraph the chief postal officer in Auckland that the plane had flown over. And I think that’s sort of an interesting thing for them to do—the flight was only about 100 miles. It went from Auckland north to a town called Dargaville and they achieved that in about an hour and a half. But, the one thing that I thought was sort of curious was that they wanted a route to fly that was close enough to water that, if there was a problem with the engine especially, they’d be able to land in the water; that they didn’t want to be too much over land so it was a wonder about the engine at that point. But, anyway, they did that. And then perhaps one of the most charming—I know I say charming all the time—but I do find it all very charming in a historical sense. They did transport a lot of passengers. Now, you can imagine flying back in those days was expensive and the people that would use the flying school’s planes to fly around were wealthy people—businessmen in Auckland or doctors and priests and bishops liked to fly to get to and from parts of their parishes. One of the most prominent citizens in the Auckland area that used their services extensively was the bishop—the Catholic bishop of Auckland—and he and George Bolt flew throughout the island. They even went down from Auckland, which is near the north side of the north island, all the way down to the mid-south island on the west coast. So that was actually a good long flight. And then in 1920, the two of them covered about 240 miles in one day, which, once again, set a record for the greatest distance flown. But, reportedly, the bishop really liked flying and I hope you can get this photograph, too, Sean—a great photograph of the bishop sitting in the plane.

00:11:47

What’s curious is that even though the B&W only has two seats, there’s three people in the plane. It almost looks as if the bishop is sitting on the plane itself, because he’s up very high, with a great smile on his face. But he really enjoyed it; much nicer than riding a horse or a wagon on some of the very uneven ground in all the flat parts of New Zealand, so he was a very happy person to be able to fly. They made a lot of visits that way and sometimes when they would land at a place where they were delivering mail and maybe when the bishop had parishioners to visit, the plane, itself, became the biggest attraction for people on the ground—especially if they’d never seen an airplane before which, more than likely, they hadn’t. So it was quite a big deal.

SM: Your story about the tracking with the telegraph just makes me think of now you’d just get on the radar website and watch the plane with your loved one coming to land. It’s kind of the world’s first radar tracker.

00:12:50

LC: There you go.

SM: So you talked a bit about the records this plane set. Why don’t we take a step back and take a look at New Zealand’s aviation history in general and how the culture developed around there? As you said, it’s surrounded by water; it’s islands; there’s a bunch of mountains, so I bet that airplanes became pretty important to that area.

LC: They did, definitely. Although—and this is true in other countries—but after the 1st World War, interest in aviation really sort of died down some. But there were people who were really interested in aviation. I mean, as early as the late 19th Century, there were aero-clubs being created. A lot of people would fly gliders and down, for example, on the south island on the east coast, the major town is Christchurch, and it is on the ocean but there’s a spine of mountains that go down the central part of the island. There’s a nice broad plain in the middle and that’s where a lot of these people flew. And one man who was from the Christchurch area, named Richard Pearce, is credited as being the person to build the first airplane in New Zealand. Unfortunately, he was working sort of in isolation; somehow, nobody else was interested in building planes around 1902 and 1903, but he did a lot of research and he built a very nice little microlight plane, which kind of got lost in history until parts of it were found in the 1950s. And then his role in New Zealand aviation was recognized. But he built this nice little plane. It only flew, kind of like the Wrights’ plane, it didn’t fly very fast. But New Zealanders believe that he achieved powered flight in a heavier airplane, then—before the Wright brothers did—because he was flying as early as 1902 and people saw him flying his plane. But he didn’t believe that he had beat the Wright brothers’ record. In fact, he felt that his really first controlled flight was a couple of months after the Wright brothers flew their plane. I find it interesting that he did not feel that he had done that, although other people did. But there’s some New Zealanders who, today, still believe that he beat the Wright brothers at their own game.

00:15:08

SM: Yeah, I think that there is an interesting claim I’ve noticed—people who claim the first flight for their home country—that the person who they claim flew before the Wrights doesn’t generally claim to have done that.

LC: Oh, yeah.

SM: It’s other people, later, who claim it on their behalf. Okay, so the flying school got their use out of at least one of the planes and so what happens next?

LC: Well, you know, by about 1921, they decided that the planes just weren’t as useful. They would kind of outlive their life span and they had other planes that they had purchased. And then, as I mentioned before, aviation just kind of lost interest; people lost interest in aviation. And so finally, they weren’t able to keep their business together. And so the two Boeing planes were retired in 1921 and then three years later, the flying school closed and the government took over the school, the airplanes, and all of that.

00:16:18

Now, the government didn’t have any use for seaplanes because supposedly the New Zealand Air Force didn’t have a base for seaplanes so Boeing planes were even less useful at that point. And they had been well-used, you know. They were built in 1916; when they were sold in 1918, Boeing had told them that the planes weren’t in pristine conditions. So by 1921, after all of the flying that had been done, I imagine they were pretty well-worn. So the government, then, took the planes and took them over to an area called North Head and—you’d have to look at a map to find it—but if you envision a large bay with Auckland on the south side of the bay, across the bay is a small protuberance, not really a peninsula but sort of like that, called North Head and it’s on the very northeast corner of that area. It had long been a military site because back in the 19th Century, they were worried about the Russians invading and so they built a small military site there. And, interesting, to me, it looked very much like Fort Townsend on the Olympic Peninsula, in terms of the concrete bunkers they built and the gunning placements up on the top, so just imagine that in your mind—kind of a round mountainous area.

There were a number of caves underneath it and then the Army at the time had built a few tunnels, so a place where they could take the planes and store them for a while, which they did. But, then, reportedly, in 1927, they took those two planes and three other planes and took them down to the shore and burned them because they had no use for them, and that seems to have been the end of the B&W. But it was a story that didn’t end there.

SM: Yeah, you’d think that would be it. I mean, how many 100-year-old planes are still around? Heck, the Wright flyer on display at the Smithsonian is mostly replaced parts.

LC: Yeah, exactly.

SM: So you, as a docent, we get people—I think you already said this—we get people from all over the world, including New Zealand, and you start hearing things from people.

00:18:46

LC: Yes, it is interesting. In fact, when Jan and I went to New Zealand on vacation, the first place that we stayed, a B&B, over on the west coast, the owner was a big aviation nut and when he found out we were docents at the Museum of Flight, he was so excited. He couldn’t stop talking about the B&Ws because a lot of people believed that they were not burned in 1927, but that they were put in the caves or the tunnels underneath North Head and that they’re still there. So this has led to, over the years, a huge conspiracy theory; I preface, it’s not very nice to say that but it sort of seems like it’s that, to me, where a lot of people believe that the planes are there but the government, for whatever reason, won’t tell them that they’re there. And so, over the years, in the 20th Century, starting in 1959, there have been investigations about whether the planes are there or not.

00:19:46

SM: So where did this—your own sleuthing—lead you in this story?

LC: Well, there’s a lot of documentation about what happened as 1959 is a significant year because it was about the 40th anniversary of that first flight of airmail in New Zealand. And then the centennial—semi-centennial—of the Boeing Company was coming up and since people had always talked about the fact that the Boeing planes were still there, there was an investigation done. The people at Boeing wanted to know if the planes were there. And they did a very careful search of the tunnels on North Head. They checked the old Army records to see if they could find out if there was a record of the planes being burned. They interviewed a major who was still around who was involved with setting fire to the planes and I think one of the big things that have led a lot of people to think that the planes may still exist was that they found a few heavily corroded metal pieces on the beach, at North Head, that were “easily recognizable as airplane parts.” In the beginning, George Bolt, who was that pilot for the flying school, thought maybe they were from the B&Ws, so they sent them to the Boeing Company to research them. But the Boeing Company was really certain that these parts were not from the B&W.

So the conclusion of all of that was that the B&Ws were burnt in 1927. But there were still a lot of people who really wanted the planes to be there, I think. And then you have the things that happened; that people will get into and even though the area was closed off for many, many years, people somehow got access to the caves; they would get ropes and ladders and climb down into the caves and they would come back out and say they saw crates that had airplane symbols on them and all sorts of things happened. And so people were certain that there were planes down there. So, in 1979 or 1980, they did another investigation to the same result: They did not find anything. And, of course, there were still some people who didn’t believe that and then in the late 20th Century, about 1996, there was a filmmaker who wanted to make a film about the B&Ws and he wanted to get access to the tunnels to see for himself if the planes were there.

00:22:24

Well, the government wouldn’t allow it and so he took the government to court and there were two court cases and all sorts of investigations were done. There was a man who wrote a book about the controversy suggesting that the planes were there and they were being hidden and on and on and on. In fact, there was even at one time—I checked recently, and it’s not there anymore—but there was a website about this whole thing that talked about all of this. It was called the Hijack of Boeing One. So lots of conspiracy theories going on. But, finally, the court cases were settled and the chief justice made a very thorough report of what had been presented in evidence during the court cases and she said that she was sure that there were no planes in the caves or in the tunnels on North Head and that the B&Ws had been burned in 1927. However, I don’t think that still has stopped some people from really wanting to believe that the planes were still there.

00:23:29

SM: People want to believe all sorts of things.

LC: They do.

SM: Especially around aviation—lots of mythos, Area 51 style, I guess.

LC: I guess, yes, that’s exactly right.

SM: Well, what we have at the museum is not the original B&W, obviously, so what is hanging in the Great Gallery? Because there is a B&W hanging there.

LC: There is. And it’s a wonderful, wonderful plane. It was built as a replica for the 50th anniversary of the Boeing Company. Since they couldn’t get the real ones, they had these replicas built. And it’s not exactly the same because it has some different parts and things like that, but it did fly in 1966. And we were very lucky to get one of the ones that was built and it’s a very handsome plane. It’s hanging in the entrance to the Great Gallery, so as you walk in, you see the reproduction of the Wright flyer. And then right above it is the B&W replica and it’s just so handsome. You can really see the floats at the bottom; can’t see to the inside very well, which is unfortunate but there’s some good photos of it on the museum’s website and certainly the Boeing Company website—and all over—because everybody just loves the B&Ws.

SM: Well, thank you for taking us on this 100-year journey, Leslie.

LC: You’re welcome. I love it.

SM: Are there any other thoughts or things you want to share about the B&W or this mystery, or anything, as you’re wrapping up?

00:25:06

LC: Not that I can think of. I just think it’s kind of fun. I’m glad to know how the B&Ws got to New Zealand. It kind of ties the whole story together and, for me, that’s kind of important.

SM: Absolutely. Your reference to that photo of kind of the old and the new, it reminds me of a photo in our own archives—our digital archives, in fact, so people at home can see this. It’s just a photo of the episode, I guess, but it’s just airplanes at an air show, possibly that the first one where Bill Boeing saw his first plane and it’s just people with their horses watching a plane go over.

LC: Oh, yeah, it’s great, isn’t it?

SM: Absolutely it is. It makes me wonder if, in 100 years, pictures of people in cars looking up at airplanes might look quaint to my great-grandchildren.

00:26:02

LC: It might definitely be; or people in jet packs flying around and looking at automobiles down on the ground.

SM: Absolutely. It’s a good reminder to stay humble.

LC: Definitely.

SM: Well, Leslie, thank you so much for your time and for sharing this story.

LC: Absolutely.

SEAN MOBLEY: Thanks for tuning into this episode of The Flight Deck—the podcast of the Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. Double thanks to you who have made financial contributions to the podcast and, by extension, to the Museum of Flight. You keep this thing going; especially right now as we continue to be closed to visitors. You can learn more about supporting the podcast through a donation in our Show Notes. Next time you’re at the museum, when you enter our Great Gallery, look up right as you enter and you’ll see our replica of the Boeing B&W so you can get a sense of the aircraft for yourself. In the meantime, we have a snazzy photo in our digital collection of the B&W, either preparing for take off or after landing on its watery runway. And I’ll put a link to this photo, which is, again, over 100 years old, in the Show Notes. If you like what you heard, please subscribe to the show and rate and review us on Apple Podcasts or wherever you downloaded us from. You can contact the show at podcast@museumofflight.org Until next time, this is your host, Sean Mobley, saying to everyone out there on that good earth, we’ll see you out there, folks.

END OF PODCAST