Paperclip Family

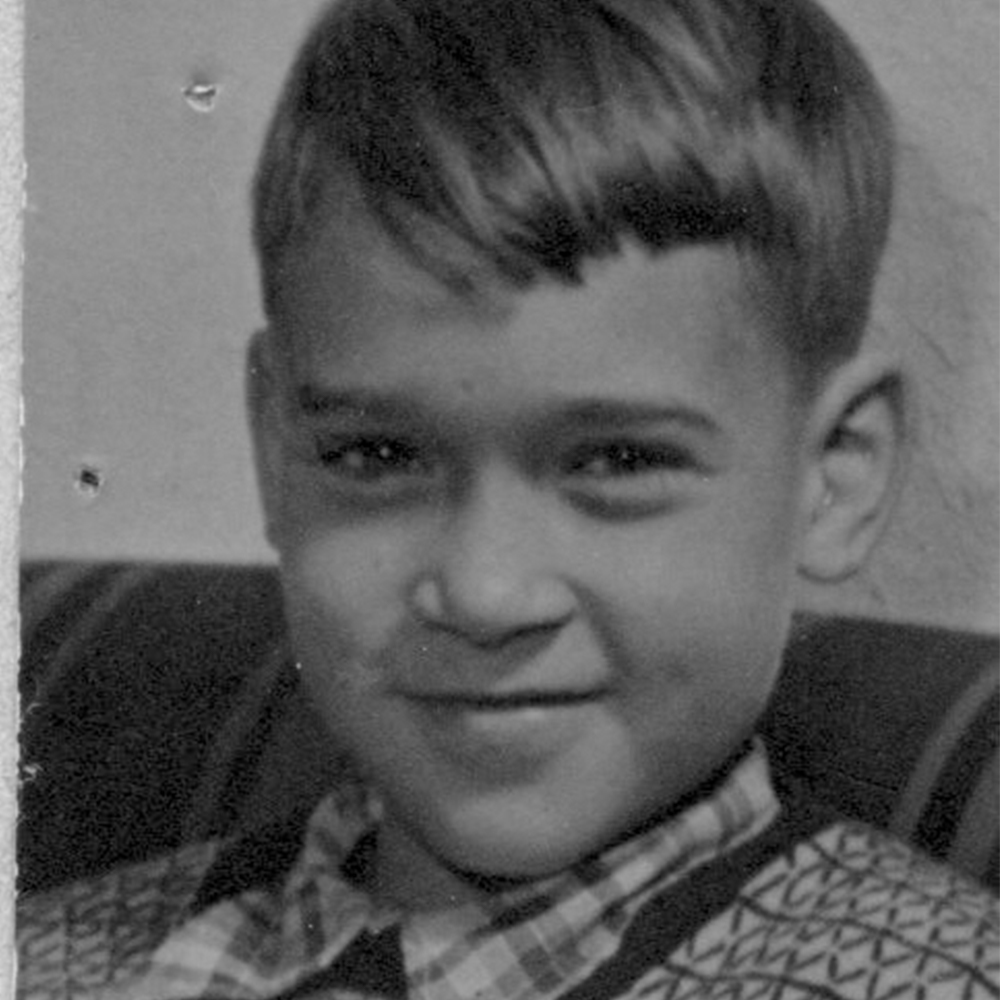

This week’s episode of the Flight Deck Podcast is the first in a series associated with the Museum wide initiative to feature untold stories in honor of the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II. Today you will hear from former Museum of Flight volunteer Reiner Decher who was a young boy in Germany during WWII. Reiner recalls the end of the war through the eyes of a child, escaping Germany with his family through Operation Paperclip.

Reiner’s father worked in aviation developing cutting edge technology for Junkers Aircraft and Motorworks in Dessau, Germany. After the war, Russia and the United States wanted to employ the greatest German scientists and engineers, Reiner’s Father was one of those selected. Hugo Junkers was an aviation pioneer who started building aircraft during the end of WWI. His company built airplanes, engines and even spawned Lufthansa Airline. During his lifetime Junkers refused to work for the Nazis, sadly he was not able to prevent them from using his technology when he died in 1935 before the beginning of World War II. The city of Dessau where Junkers was located was captured by the U.S. and had to be vacated to the Russians, becoming a Soviet Occupation zone.

Operation Paperclip consisted of gathering people of various technologies. The American Army was interested in new technology that they had not yet developed. They were in search of the best scientists, doctors and physicists, giving Germans an opportunity to come to America. Around 1,600 people were selected to come to the states. Reiner’s father, Siegfried, decided his family would go to America before the Russians came through… They were loaded into a large truck along with two other families. Their car unfortunately crashed during its journey, fracturing the skull of Reiner’s brother. Reiner’s entire family was transferred to a local hospital where the American Army disguised his mother as a nurse to avoid any suspicion.

This delay cost his family the opportunity to go to the US, but all hope was not lost. Reiner’s father was then invited by the French government along with those spearheading the BMW jet engine effort to support France in new technological advances. His family started their new life in a small town in central France where Reiner spent most of his time growing up. Finally, there was peace for Reiner and his family, they were able to live a somewhat ‘normal’ life. He did however experience discrimination at first associated with bitter feelings from the war… that soon dissipated after the immense impact of German technical innovation on France.

Transcript after the player.

Hear more incredible stories like Reiner’s with our Untold Stories: World War II at 75 programming happening for the duration of this year. We will also be refreshing our Personal Courage Wing, incorporating rare artifacts and experiential exhibits in the theme of World War II.

Producer: Sean Mobley

Webmaster: Layne Benofsky

Social Media Specialist: Tori Hunt

Transcript

SEAN MOBLEY: The Flight Deck is made possible by the generous donors supporting The Museum of Flight. You can support this podcast and The Museum of Flight’s other initiatives across the United States and the world by visiting museumofflight.org/podcast.

[Music]

SM: Hello, and welcome to The Flight Deck, the podcast of The Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. I am your host, Sean Mobley. This episode is part of a museum-wide initiative commemorating the 75th Anniversary of VE Day and VJ Day this year. Today we are hearing a story from one of our docents, Reiner Decher, who was a very young boy in Germany during World War II. His father worked for the Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works and was developing cutting-edge aviation technology, so cutting edge that as the war entered its final days and both the Russians and the United States were snapping up German scientists and engineers, the Decher family was wooed by both governments.

00:01:11

Reiner shares his experience seeing the end of the war through the eyes of a German child and how his family's attempts to leave Germany as part of Operation Paperclip was foiled by a horrible accident.

[Music]

REINER DECHER: I was born in 1939. I was born, in fact, seven days ‒ or nine days before the first jet airplane flew.

SM: [Chuckles]

RD: So I'm as old as the jet age. So you can imagine 1944 I was five years old, and the situation in Dessau in Germany where we were living had gotten pretty bad in the sense of the Allied strategic bombing that was taking place that my father as well as some of the other engineers that were working on the Junkers engine decided to move all the families out into the woods, basically. And so we ended up living in a really small village in the Harz Mountains where the threat of bombing was much, much reduced, and so we missed some of that war. My father bicycled the 60 kilometers or so to visit us every now and then.

00:02:21

SM: So, for those who might not be familiar with Junkers, can you share a little bit about the company?

RD: Yes, I can. Junker, Hugo Junkers, an aviation pioneer, I think he really qualifies to be an important person in that aviation history. He built airplanes during the end of World War I and quickly realized that after World War I, success in aviation was going to be in commercial aviation. His company not only built the airplanes but they built the engines as well, as well as he created an airline that later became Lufthansa. He had no love for the Nazis, and in fact, they tried very hard to convert all his factories and airplane building capability into the war machine, and he refused. And, unfortunately, he also died at age 76 ‒ I think he was ‒ in 1934 so that right after that the Nazis jumped in there and took it over. And there are many airplanes, war airplanes, that bear the Junkers name that he would really be upset to know to have been constructed.

SM: So, as the war was wrapping up and the Allies were closing in on both sides and on Germany, Operation Paper Clip started up. Can you give a big picture view of what operation Paper Clip was?

00:03:39

RD: Yes. Operation Paper Clip consisted of gathering up people from various technologies where the American Army ‒ or military I should say broadly ‒ was interested in the technology that might ‒ they might not have had developed yet, and my father was on that list as well as were all the principals at the Junkers company, as well as the leader of the BMW Group in the jet engine side of things. And there were doctors there. There were opticians there. There were physicists of various kinds and, of course, the rocket people with Wernher von Braun. There were like 1,600 names or so. They were basically offered an opportunity to come to the United States.

SM: What did your dad do at Junkers to earn him a spot on this list?

RD: Father was ‒ he graduated in 1937 and ‒

SM: What was his name?

RD: Siegfried, Siegfried Decher. When Junkers got the contract to build the jet engine, they assembled a team, and he was on that team. He was basically focused on the controls aspect of it.

SM: The war is coming to a close, and your family ‒ your dad is selected for Operation Paper Clip. Can you describe kind of the immediate aftermath, your family preparing to go and trying to get out before the Russians are starting to sweep in also ‒

RD: Yes.

SM: ...from the other side?

00:04:56

RD: Yeah. The family couch, my father said at one point, had sitting on it American colonels, Russian colonels as well as French ones, all trying to talk him into either staying there, which turned out he didn't do, but that was an option. The Russians were very keen and understood what the technology was that these people had a handle on. Ultimately, my mother would have nothing to do with the Russians because there were lots of refugees coming from the East reporting about what conditions were like from on the Russian side, and she wanted nothing to do with that and so ‒ and besides, our family was in the West anyway, so it was a decision that made itself. It was essentially established that we were going to go back with the Americans. We were given an allotment of 300 lbs. of goodies to take with us, and we were loaded with two other families into a big Dodge 2.5 ton truck, and it was ‒ this was in June, June 21, 1945, and on July 1, the Soviets were going to be occupying the country, so it was time to move on. As it turned out, the driver of our truck ended up getting the truck into an accident and flipped it over, badly injuring my younger brother, who needed about four or five months to recover from the injuries. He had a triple skull fracture that really set him back quite a bit. And we were all taken, all 10 people that were in that truck, were taken to a local hospital. The truck, by the way ‒ This was a beautiful summer day. The truck didn't have the canvas covering on the top. It was riding in a convertible, kind of. It was a beautiful, lovely day.

SM: How old was he?

RD: He was three.

SM: Okay.

00:06:44

RD: We were transported to this hospital. The American Army disguised my mother as a local nurse so that Russians wouldn't get suspicious. My father and I continued with the convoy to the West. And my mother routinely visited my brother in the hospital and walked by the American Field Headquarters that were there and one day found that the flag was gone and the Americans were gone, and so she said to herself ‒ beep.

[Laughter]

SM: So she is now in Russian territory.

RD: Not yet.

SM: Not yet, but they’re on their way.

RD: Day, day before, but they're all there. They're around. So she went back to the hospital to be with my brother, and a couple of hours later a doctor is running around the hospital trying to look for her and to tell her that there was an ambulance outside with two paramedics and a stretcher, and she said, “I'm on it.” [Laughs] And they left as soon as they could package him.

00:07:45

And she said while they were driving out they saw the new Russian occupation forces coming in, and it was ‒ she breathed a big sigh of relief.

SM: But that delay ended up costing your family the chance to leave to the US.

RD: Correct. Correct. My brother had to continuously lie on one of his sides ‒ I forget which one ‒ to let the ear drain whatever was going on in his skull, and I'm told that we ended up in a field hospital in Bad Kissingen near Frankfurt where he was apparently lying on a bed next to the window. He could look outside, and I was explaining to him what all the American Army vehicles were that were cruising by or parked nearby. It was ‒ I had no idea I knew all that stuff, but here I was. [Laughs] But he was finally discharged from that field hospital. The other people went to a little town called Oberursel, which is the name of the town where all the rotary engines that were powering World War I airplanes were built. It was a big factory there, and that's where they were assembled, and we never made it to that town. The French Government had no gas turbine industry whatsoever back in the 1945 time period. They had obviously a very rich history of aviation, and they wanted to get into this new technology very badly, and so they interested a leader of the BMW jet engine effort. BMW was designing a jet engine that was supposed to be an advanced version of what Junkers was doing, and that group of people was more or less invited by the French Government to go to France, and my father joined that group because he no longer could join the American group.

00:09:37

We were put into a small town in the middle of France on the Loire River, and that's where I grew up, in Central France. The time period was a very happy one for my parents because, first of all, it was peace time, and there’s food to eat, and things were much, much better, and I enjoyed it, going to ‒ went to schools in France. Initially, the period was somewhat stressful because the German-French relationship wasn't all that great ‒

[Laughter]

RD: ...after the war, as you could imagine, and I had rocks thrown after me on my way to school and things like this, but this little village was small enough that the 150 or so German engineers from BMW had a pretty important economic impact on the village, and within a year all of those animosities had more or less evaporated because people got to know one another. And, in fact, before that whole program was over, there were, like, five or six marriages between French and Germans in those two communities.

[Music]

SM: Thank you for tuning into this episode of The Flight Deck, the podcast of The Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington. You can learn more about the Museum's commemoration of the 75th Anniversary of the end of World War II, including the grand reopening of our newly refreshed World War II exhibit and an amazing lineup of public programs on our website, museumofflight.org.

00:11:15

If you like what you heard, please rate and review the podcast on Apple Podcasts or wherever you downloaded us from and share it out with your friends. We appreciate your help spreading the word. You can contact the show at podcast@museumofflight.org.

Until next time, this is your host, Sean Mobley, saying to everyone out there on that good Earth, “We'll see you out there, folks.”

END OF PODCAST