The World's Worst Aircraft Disaster

According to two separate reports in 2017, from a Dutch consulting firm and the Aviation Safety Network, 2017 was the safest year on record for commercial air travel. But 40 years earlier, it was a different story. The aviation industry endured years of horrific accidents, the worst ever being the Tenerife Airport disaster. A combination of circumstances involving weather, a terrorist bomb threat, poor communication from air traffic controllers,an impatient pilot, and radio crosstalk came together to allow the collision of two Boeing 747s, resulting in the deaths of 583 souls. Flight attendants and rescue crews were able to pull 70 people from the wreckage, and the black-box recordings revealed how and why the deadly accident happened.

The Detour

At 9:01 A.M. on the morning of March 27, 1977, a KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 747, PH-BUF, Rijn, departed Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam bound for Las Palmas de Gran Canaria Airport on Grand Canary Island. Piloted by Captain Jacob van Zanten, KLM’s well-respected chief training captain for 747 crews, the plane was about to end a four-hour journey and land at Las Palmas. However, this plan was altered due to a terrorist bomb threat at the Las Palmas passenger terminal at 1:00 p.m., accompanied by a phone-in threat about another bomb. The airport closed and all flights were diverted to Los Rodeos Airport on the island of Tenerife, about 200 km northwest of Las Palmas. The KLM jet landed at Tenerife at 1:10 P.M. and air traffic control directed the KLM aircraft to park on the holding apron for runway 12 at the end of the taxiway. The KLM 747 was soon joined by a Pan Am 747, N736PA, Clipper Victor, piloted by Captain Victor Grubbs, which had departed Los Angeles the afternoon before.

The Waiting Game

By the time the Pan Am 747 had landed, Captain van Zanten was getting restless and concerned about the time he was losing on Tenerife. In the years leading up to 1977, there had been a series of near-fatal incidents on the KLM system that were attributed to crew fatigue, so KLM’s captains no longer had the authority to work their crews beyond normal duty hours. Van Zanten was afraid he wouldn’t get his 747 to Las Palmas before those hours were exceeded, which would have left him open to prosecution back home.

Van Zanten called the airline and was informed that he and his crew could remain on duty until 6:30 p.m., local time. Relieved by that information, Captain van Zanten then decided to refuel his jumbo jet while waiting on runway 12’s holding apron. Just when he began to refuel, however, Las Palmas reopened and aircraft began departing Tenerife.

Three smalleraircraft on the holding apron, a 727, a 737, and a DC-8, could get past the KLM747 as it was refueling, but the Pan Am 747 could not: it was stuck on the ground until the KLM plane finished refueling.

At 4:28 p.m.the KLM crewcalled the tower and requested permission to taxi to runway 30. At this point, a heavy fog beganrolling into the airport and visibility was down to about 1,000 feet.

The tower instructed the KLM crew to back-taxi down runway 12, make a 180-degree turn on the threshold of runway 30, and hold.

At this same time, the Pan Am 747 had also been cleared to back-taxi down runway 12 and to follow the KLM airplane. The KLM crew completed its take-off checklist, and then Captain van Zanten did something unexpected.

The Fateful Choice

At 4:35 p.m., van Zanten spooled up the engines and started his take-off roll. First officer Klass Meurs told him, “Wait a minute—we don’t have an ATC clearance,” so van Zanten stopped the airplane and Klass requested their airways clearance. The tower provided KLM’s airways clearance; Klass read it back and then, after van Zanten had already started the takeoff roll for the second time, Klass said, “We are now at take-off.”

According to Air Traffic Control terminology, this statement is too ambiguous to give any real information. It could have been a position report, or it could have been an activity report. The tower incorrectly concluded it was a position report and said,“Ok, standby for takeoff. I will call you.”

The Miscommunication

Just as the tower was replying to the KLM jet, the Pan Am 747’s first officer, Robert Bragg, keyed his microphone to report that the Pan Am jet was still back-taxiing on the runway. The tower controller replied, “Roger Pan Am 1736, report the runway clear.” First Officer Bragg then said, “OK, will report when we are clear.” Tragically, Bragg’s radio call to the Tower took place at the same instant that the tower was telling First Officer Klass, “OK, stand by for takeoff. I will call you.” All that the KLM crew heard was the controller’s first word, “OK,” which was followed by the squeal of radio crosstalk, as First Officer Bragg keyed his microphone, frantically reporting that the Pan Am jet was still on the runway.

Van Zanten was already accelerating and they were 20 seconds into their takeoff roll when the flight engineer on the KLM jet, Willem Schreuder, heard the tower reply, “Roger, Pan Am 1736. Report the runway clear,” and First Officer Bragg’s response: “OK, will report when we are clear.” Schreuder then asked Captain van Zanten, “Did he not clear the runway—that Pan American?” Van Zanten and First Officer Meurs responded, emphatically and in unison, “Yes,he did,” and kept accelerating.

The Crash

Through the fog, Pan Am’s Captain Grubbs could see the KLM jumbo coming at them with its landing lights shaking, so he desperately tried to spool up the engines and pull off into the grass. But he missed the third intersection, partly because there was confusion about which was the third intersection, partly because the third intersection would have required the 747 to make two 135-degree turns, first to the left, then back to the right, and because there was a safer, 45-degree intersection shortly beyond the third intersection. The airport’s outdated infrastructure wasn’t big enough for the jumbo jet to take the third intersection easily.

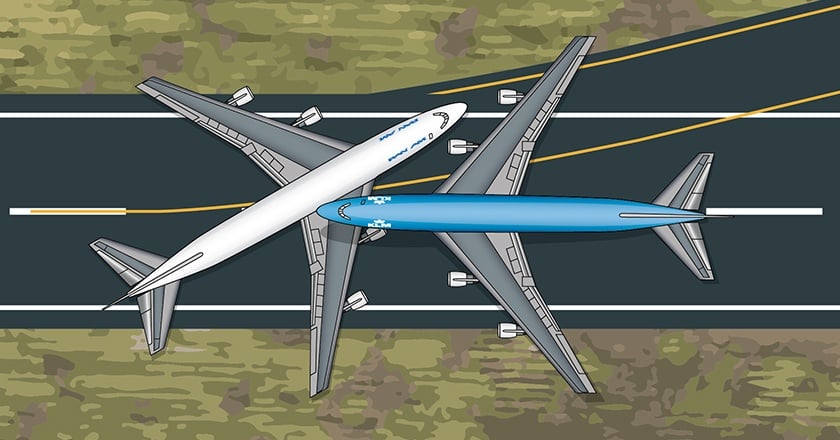

Grubbs was trying to pull into the grass short of the fourth intersection when the KLM crew finally saw the Pan Am jumbo. Van Zanten pulled on the yoke to get airborne, but didn’t have enough space to avoid the Pan Am jet. The KLM 747’s landing gear and three of its engines ripped off the top of the Pan Am jet, and both jets then exploded into flames.

The KLM jet remained airborne for about 500 feet before slamming back on to the runway, skidding another 1,000 feet, and exploding before any of the cabin doors could be opened. The tower heard the explosion but didn’t see what happened. The airport sent out rescue crews who came down the foggy runway to the KLM jet first, not realizing that there was alsoa second plane—the Pan Am jet— on the runway. Everyone on the KLM airplane died. Seventy survivors were rescued from the Pan Am jet, nine of whom died later.

The Recordings

KLM hoped that the cockpit voice recorders had survived the accident because KLM believed Pan Am was at fault and that KLM’s salvation was in those recorders’ tapes. Because the fire didn’t reach KLM’s cockpit voice recorder, located in the back of the plane, it was possible to salvage it from the KLM wreckage. The recovered recorder, along with the flight data recorder, was packed in 55-gallon steel drums, wrapped in fire-retardant material, and sent to Redmond, Washington, headquarters of Sun Stream Corporation, the makers of the recording devices, for analysis.

When the recordings were analyzed, investigators identified the radio crosstalk and van Zanten’s impatience. Ultimately, KLM was deemed to have been primarily responsible for the accident, with secondary responsibility assigned to the Pan Am crew (for failing to exit runway 12 at the third intersection), and to the Los Rodeos Air Traffic Controllers (for poor command of English and use of non-standard terminology).

The Lessons

Accidents like this are never caused by one single issue, but rather the culmination of unrelated, disparate events. If the bombing hadn’t occurred, the planes wouldn’t have been redirected to Tenerife. If the Pan Am jet weren’t late from Los Angeles, it would have landed at Las Palmas before the bombing. If the KLM crew hadn’t decided to refuel on Tenerife, they would have left earlier, in better weather. If the fog weren’t so dense, the two 747s may have had time to avoid each other. If the radio crosstalk hadn’t happened, both the Pan Am and KLM jets would have known each other’s exact locations.

In ensuing years, airports installed surface-detection radar to allow air traffic controllers to follow all aircraft on the ground, even when they can’t be seen. Modern avionics for cockpits make an automatic annunciation if there is another plane occupying the runway or approaching it from the air. With these advancements, aviation safety has increased over the years, and we can hope that perfect safety records continue into the future.

This story was adapted from a storytelling session by aviation expert Bob Semlow. Check out a story for yourself next time you visit the Museum!