Stories from a Career B-52 Pilot

Major Paul Grubbs wasn’t always a fixed wing aficionado; he actually flew helicopters for many years before the opportunity to pilot a fixed wing fell into his lap. But, after six and a half years and nearly 1,800 hours of flying the B-52, Paul wouldn’t trade the experience for the world. Here’s what he has to say about flying this world-class bomber.

Early Days

After Paul completed Officer Training School and graduated in 1972, he began flight training at Fort Wolters, Texas and Fort Rucker, Alabama and gained experience flying H-3s. Beginning his career with the 317thSpecial Operations Squadron, Paul later joined the Alaskan Air Command’s 5040thHelicopter Squadron (converted to the 71stAerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron) at Elmendorf AFB, just outside of Anchorage, where the best part of the job – other than flying 20 search and rescue missions garnering 13 saves and 17 assists - was flying low to admire the rugged terrain, blazing sunsets and rare wildlife in the area.

Despite all of his training, Paul just missed his opportunity to join the Vietnam War efforts. The SpecOps unit he was assigned to in Vietnam was actually on its way back to the U.S. right after he earned his wings. But Paul wasn’t ready to give up on a career in the Air Force any time soon.

Transitioning to the B-52

Paul admits that although he was never a huge fan of the fixed wing aircraft, he did enjoy certain aspects of fixed wing training. Paul remembers: “I really didn’t enjoy fixed wing training until I got into the formation phase in T-38s. Because you had to be precise in trying to stick with and follow the guy in close trail. Like what you would see with the Thunderbirds where you’re tucked in on the wing or underneath, you stay right with them, so that was challenging. Then they went to what they call extended trail, which is more of what a fighter does. You’d be out there trying to figure out how you’re gonna stick with him, stay where he’s going. And you learn to pick up little things, like you’d see the wing tip flex and you’d see he’s pulling, so I’m going to start pulling.” This part of his training schedule was far more exciting than the routine take-off and landing exercises he was tasked with completing.

After his fixed wing training, he and his colleagues were allowed to choose their specialty aircraft from a pool offered by the Air Force. While you might think everyone would love to be a fighter pilot, Paul and his colleagues were not excited about the idea, and his superiors were shocked. “We were used to crew concept,” Paul recalls, “and I didn’t want to be flying by myself for the rest of my life.” That, in addition to the fact that Paul had a young family he wanted to return to daily (no long deployments), steered him away from fighter jets and into larger jets.

But he wasn’t too enthusiastic about piloting a plane like the KC-135. “KC-135s would go on deployments quite a bit,” Paul explains. “They would have more temporary duty. It’s fun if you’re by yourself, but I had a family that I wanted to stay close to.”

So, Paul finally decided on the B-52, and he flew both the G and H models.

What He Likes About the B-52

After so many years flying helicopters, the first of which just had 4 little instruments to read, it took some getting used to for Paul to navigated the complex panel of gauges and meters that are found on the B-52, aka BUFF. Cross-checking instruments took longer, but Paul got used to the BUFF life, which he describes as “hours of boredom interrupted by a few moments of sheer terror.”

A typical training mission would involve take-off, air refueling, low-level navigation, and bomb runs. After low-level bomb runs, Paul would pull the plane up for high-level simulated releases while the electronic warfare officer completed tasks related to enemy threat systems. This routine was challenging enough to keep Paul busy. “It was definitely challenging at the low level, and bouncing around in bad weather wasn’t fun,” Paul adds. His navigator wasn’t having an easy time of it, either, and Paul remembers him having to vomit during every mission, “We would ask him, ‘Are you ok? Are you sure you want to do this?’ and he would be like, ‘Yeah, I want to do this.’”

Paul also got a kick out of working with KC-135s during the refueling process, a midair dance that reminded him of the formation flying he used to do during training. “We would get a little bow wave going, so it was like another precision maneuver during formation flying. You had to get through that bow wave that pushed the KC-135’s tail up. When you get better you can try different things. You’d say, ‘I have only this much power,’ or ‘These engines are out.’”

As the boom operator extends the boom out from KC-135, Paul had to control his speed and position by tracking a pair of yellow stripes underneath the tanker and the red-to-green bands on the boom.

B-52 Quirks

Aside from flying his favorite refueling missions, Paul looks backs with some fondness on the quirks of the B-52 itself. One of them being the fact that although it’s such a huge plane, crew members can’t really stand up in it (except by the ladder that leads up to the cockpit).

There wasn’t anywhere to cook food on the G-model — no microwave, no hotplate. But it could protect you in the incident of a nuclear fallout. The cockpit has silvery-looking radiation-proof curtains (see photo below) that reflect blinding nuclear light that the pilot would close around the cockpit in the case of a nuclear incident. The cockpit was also outfitted with low-light TVs and forward-looking infrared to help pilots chart their course.

The B-52 G and H models did not have ailerons. Paul explains that in order to turn, “you stick this big slab of metal up into the wind. The first thing it would do is pitch the nose up, so when you turn you push the yoke forward and then turn, whereas other aircraft can just do a smooth turn.”

And for landing the B-52 uses a drag chute—unless there’s too big of a crosswind. “We did have a crosswind crab system, though,” Paul remembers. “When you’re landing and there’s a strong crosswind, you have a wing down with opposite rudder, or you keep wings level, crab into the wind, and feed in rudder to align the aircraft just before touchdown. Since the B-52 wingspan is longer than the fuselage, neither one is conducive to long life. The B-52 has a system where you can crank the gear up to 22 degrees off center so you can land wings level in a crab. Once you slow down enough, you can crank the gear back to original position. It looks bizarre!”

It’s hard to imagine trying to control a huge aircraft like the B-52 in the air and on land, but as you can see from Paul’s experience, the B-52 is both a curious and powerful aircraft not meant for the faint of heart. In fact, one of Paul’s first B-52 instructor pilots told him, “Good Luck. It’s not an easy plane to fly.”

And Paul also loves the B-52 we are currently restoring for our Vietnam Veterans Memorial Park. Its tail is marked with lettering that shows it flew during Operation Linebacker, and Paul approves of its makeover: “It looks good! The 2584, a B-52 I flew, didn’t look that good on the Barksdale flight line!”

Want to learn more about our B-52 that flew during the Vietnam War? Get info about Project Welcome Home and the B-52 restoration process.

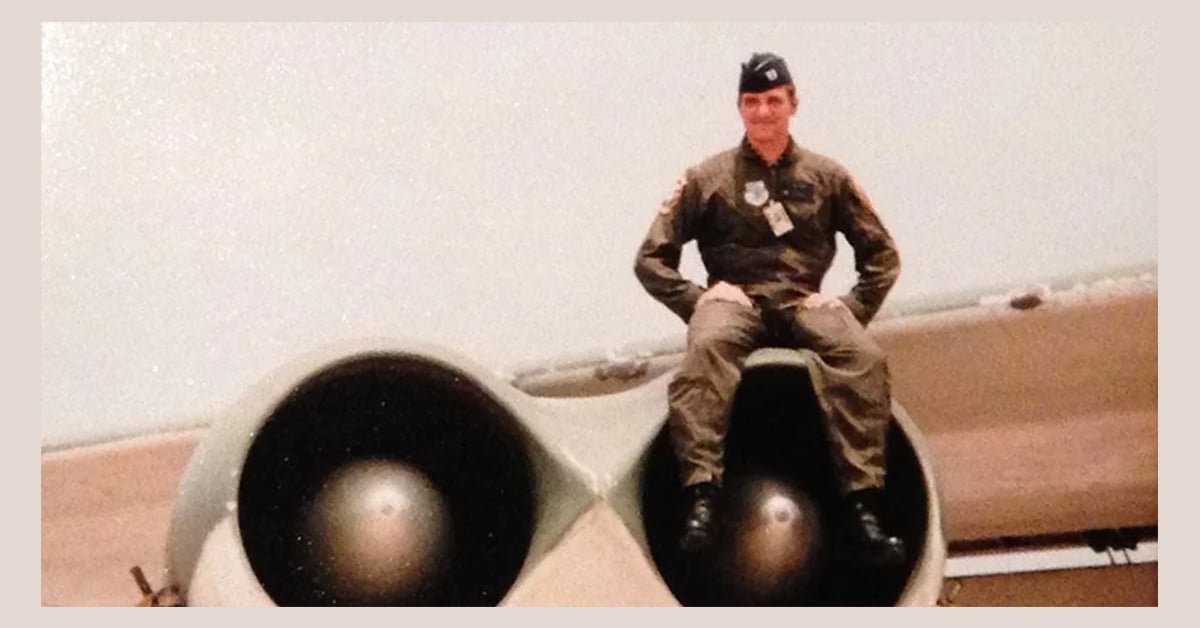

Top photo: Courtesy of Paul Grubbs

Bottom photo: Courtesy of Irene Jagla